Widening the lens: Addressing Educational Disadvantage

Tackling educational disadvantage is a subject close to many hearts across the school governance world. But making sure pupils who begin life facing more barriers to education than others end up with the same opportunities as their peers is easier said than done.

Tackling educational disadvantage is a subject close to many hearts across the school governance world. But making sure pupils who begin life facing more barriers to education than others end up with the same opportunities as their peers is easier said than done.

Perhaps one of the challenges you have faced is establishing what educational disadvantage actually means. The Department for Education’s (DfE) Governance Handbook tells governing boards they need to “raise standards for all children … [including] … those receiving free school meals and those who are more broadly disadvantaged.”

While that might seem straightforward, the inclusion of the words “disadvantage” and “broadly” carries an air of vagueness. If you relate, you are not alone! Even the experts struggle to define or agree on the term.

The reality is that while disadvantage in education is consistently reported as one of the biggest challenges that schools and trusts face, it can and does take on multiple different forms.

Search for the DfE’s explicit definition of ‘disadvantage’ and you will probably end up looking at different things in various places. In short, there is no ‘official’ definition, but the DfE instead largely makes pupil premium funding available to schools to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils based on restricted socio-economic factors. In doing so, many schools tend to look at addressing educational disadvantage through this lens.

Some of you might remember that back in 2018, NGA published Spotlight on Disadvantage, a report exploring the role of governing boards in spending, monitoring and evaluating the pupil premium. It concluded that receipt of pupil premium was not the only determinant of disadvantage; a more holistic approach was needed. Although the majority of survey respondents who contributed to the research defined ‘disadvantaged’ as those eligible for the pupil premium, other criteria were also being used in schools and trusts.

We have since heard from a number of members on the different approaches they take to how they approach disadvantage in their organisation, and together this all points to other groups of children and young people that we should be looking at in pursuit of closing the attainment gap who are statistically at a significant educational disadvantage.

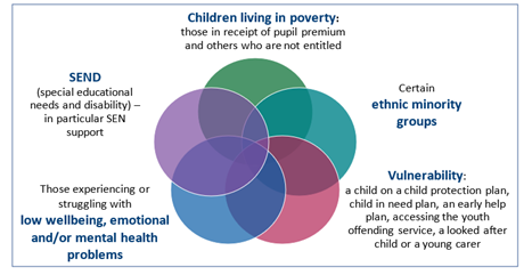

For a while, NGA has been exploring some of this in more depth and we have focused primarily on five drivers of educational disadvantage:

By focusing on these, NGA is certainly not attempting to create new labels; in fact we want to do the opposite and help drive a focus to look beyond what is widely perceived as the well-established label of disadvantage.

Defining disadvantage is particularly difficult as some groups are more at risk of educational disadvantage than others and it also doesn’t mean the same thing for everyone. For example, a newly published blog by FFT education datalab highlights that those eligible for free school meals (FSM) at school for any length of time are “less likely to go on to a positive destination than those who were never eligible and long-term disadvantaged individuals were the least likely of all”. This is just another example that shows disadvantage is a more complex spectrum than some realise.

All of these reasons are why many in the research community argue that pupil premium eligibility is too much of a ‘blunt instrument’ and should not be used as the primary indicator of disadvantage. Such an indicator is by no means universally recognised in the international community.

There are groups of pupils that have not always been the focus of the educational disadvantage conversation, and we now want to enhance the lens through which the conversation is viewed. We know many boards and their leaders have broadened their view on who may be vulnerable to educational disadvantage over the years, and this work has looked to consolidate much of that learning. By sharing it, and refining it over the coming year, we hope this will help to ensure the systems and processes in place will create a learning environment where all pupils can flourish.

To that end, we have published five toolkits along with an accompanying guide, Widening the lens on disadvantage. They are aimed at tackling disadvantage in education, identifying the link between each pupil group and educational disadvantage, signposting to resources and include questions for governing boards to explore with their school leaders. The toolkits have been produced with support from The Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), Place2Be, Two Ten Therapy, The Children’s Society and Class 13, all experts in their field and key contributors.

We would also like to provide you with the opportunity to contribute to the second edition, so if you have strategies or resources that work for your pupils and would like us to include them do get in contact with our policy and projects manager, Fiona Fearon.

We want to ensure the toolkits are practical so we are adopting the process which worked last year for the Greener Governance guidance – using our Spring’s Governance Leadership Forums to explore the topic with you, our members, before improving the toolkit with a second edition.

Sam Henson

Deputy Chief Executive

Sam oversees NGA’s policy, communications and research services, supporting NGA to achieve positive change in the policy of school governance. He is the policy lead for NGA’s work on the governance of multi academy trusts.